Table of Contents

Endoscopic instruments are precision-engineered medical tools designed to work through the narrow channels of an endoscope, allowing surgeons to perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures deep inside the human body without major surgery. These instruments serve as the surgeon's hands, enabling minimally invasive actions such as taking tissue samples (biopsies), removing polyps, stopping bleeding, and retrieving foreign objects, all guided by a real-time video feed.

The advent of endoscopic instruments marks one of the most significant paradigm shifts in the history of surgery and internal medicine. Before their development, diagnosing and treating conditions within the gastrointestinal tract, airways, or joints required highly invasive open surgery. Such procedures were associated with significant patient trauma, long recovery times, extensive scarring, and a higher risk of complications. Endoscopic instruments changed everything by ushering in the era of minimally invasive surgery (MIS).

The core principle is simple yet revolutionary: instead of creating a large opening to access an organ, a thin, flexible or rigid tube equipped with a light and camera (the endoscope) is inserted through a natural orifice (like the mouth or anus) or a small keyhole incision. The endoscopic instruments, designed with remarkable ingenuity to be long, thin, and highly functional, are then passed through dedicated working channels within the endoscope. This allows a physician in a control room to manipulate the tools with incredible precision while observing the magnified, high-definition view on a monitor. The impact has been profound, transforming patient care by reducing pain, shortening hospital stays, lowering infection rates, and allowing for a much faster return to normal activities. These instruments are not merely tools; they are the conduits of a gentler, more precise, and more effective form of medicine.

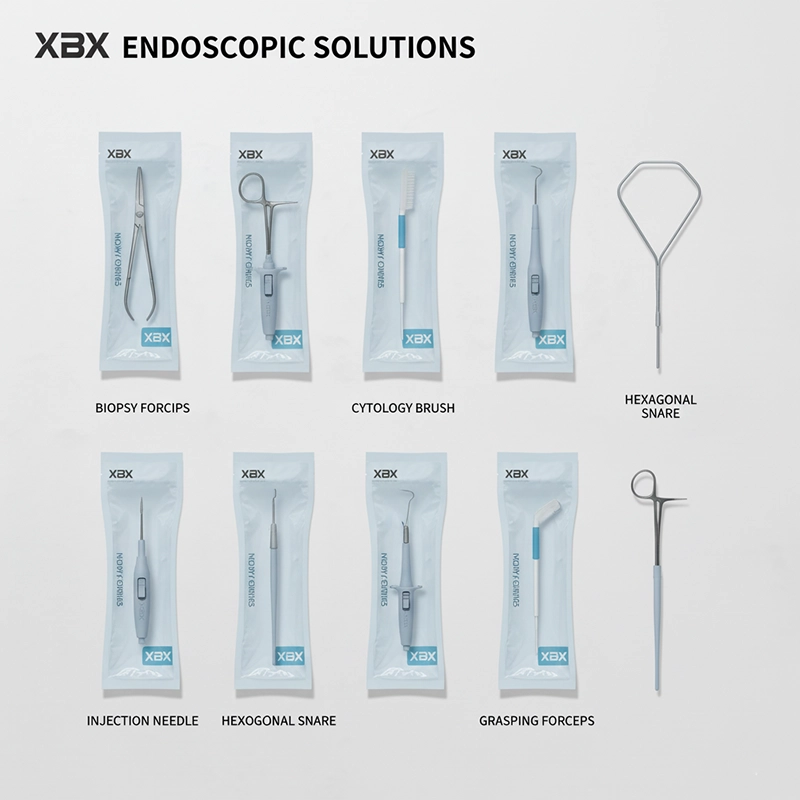

Every endoscopic procedure, from a routine screening to a complex therapeutic intervention, relies on a specific set of tools. Understanding their classification is key to appreciating their role in the operating room. All endoscopic instruments can be functionally organized into three primary categories: diagnostic, therapeutic, and accessory. Each category contains a wide array of specialized devices designed for specific tasks.

Diagnostic procedures are the cornerstone of internal medicine, and the instruments used are designed for one primary purpose: to gather information and tissue for an accurate diagnosis. They are the eyes and ears of the gastroenterologist, pulmonologist, or surgeon, allowing them to confirm or rule out diseases with a high degree of certainty.

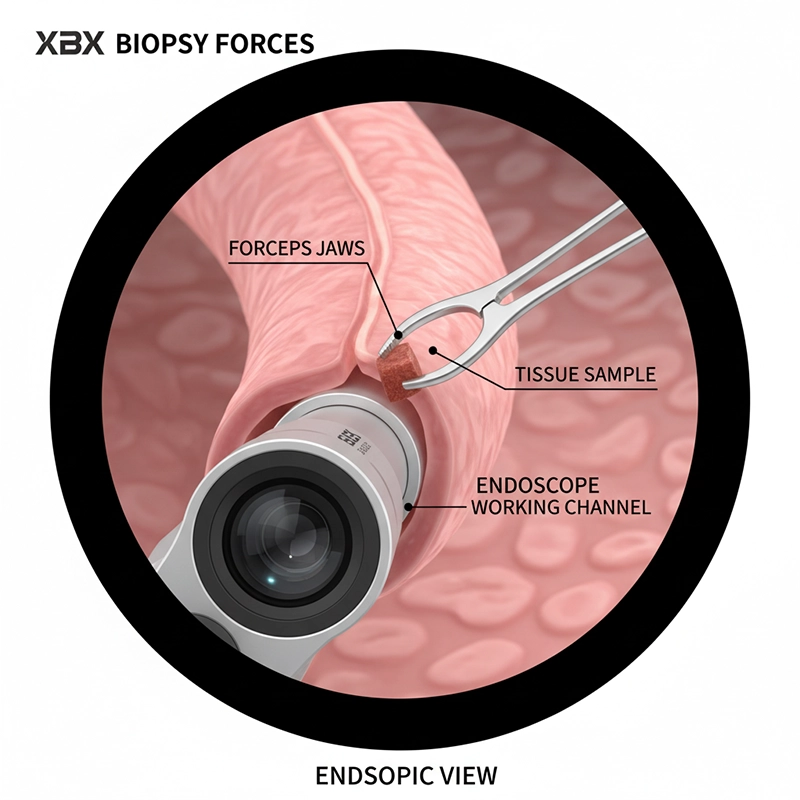

Biopsy forceps are arguably the most frequently used endoscopic instrument. Their function is to obtain small tissue samples (biopsies) from the mucosal lining of organs for histopathological analysis. This analysis can reveal the presence of cancer, inflammation, infection (like H. pylori in the stomach), or cellular changes that indicate a specific condition.

Types and Variations:

Cold Biopsy Forceps: These are standard forceps used for sampling tissue without the use of electricity. They are ideal for routine biopsies where bleeding risk is low.

Hot Biopsy Forceps: These forceps are connected to an electrosurgical unit. They cauterize the tissue as the sample is taken, which is highly effective for reducing bleeding, especially when biopsying vascular lesions or removing small polyps.

Jaw Configuration: The "jaws" of the forceps come in various designs. Fenestrated (with a hole) jaws can help secure a better tissue grip, while non-fenestrated jaws are standard. Spiked forceps have a small pin in the center of one jaw to anchor the instrument to the tissue, preventing slippage and ensuring a high-quality sample is taken.

Clinical Application: During a colonoscopy, a physician may see a suspicious-looking flat lesion. A biopsy forceps is passed through the endoscope, opened, positioned over the lesion, and closed to snip a small piece of tissue. This sample is then carefully retrieved and sent to pathology. The results will determine if it is benign, pre-cancerous, or malignant, directly guiding the patient's treatment plan.

While biopsy forceps take a solid piece of tissue, cytology brushes are designed to collect individual cells from the surface of a lesion or the lining of a duct. This is particularly useful in areas where a traditional biopsy is difficult or risky to perform, such as the narrow bile ducts.

Design and Use: A cytology brush consists of a sheath containing a small, bristled brush at its tip. The sheathed instrument is advanced to the target location. The sheath is then retracted, exposing the brush, which is then moved back and forth over the tissue to gently scrape off cells. The brush is retracted back into the sheath before the entire instrument is removed from the endoscope to prevent cell loss. The collected cells are then smeared onto a glass slide and examined under a microscope.

Clinical Application: In a procedure called Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), a cytology brush is crucial for investigating strictures (narrowings) in the bile duct. By collecting cells from within the stricture, a cytopathologist can look for malignancies like cholangocarcinoma, a type of cancer that is notoriously difficult to diagnose.

Once a diagnosis is made, or in situations that require immediate treatment, therapeutic instruments come into play. These are the "action" tools that allow physicians to treat diseases, remove abnormal growths, and manage acute medical emergencies like internal bleeding, all through the endoscope.

A polypectomy snare is a wire loop designed to remove polyps, which are abnormal growths of tissue. Since many colorectal cancers develop from benign polyps over time, the removal of these growths via a snare is one of the most effective cancer prevention methods available today.

Types and Variations:

Loop Size and Shape: Snares come in a variety of loop sizes (from a few millimeters to several centimeters) to match the size of the polyp. The shape of the loop can also vary (oval, hexagonal, crescentic) to provide the best purchase on different types of polyps (e.g., flat vs. pedunculated).

Wire Thickness: The gauge of the wire can differ. Thinner wires provide a more concentrated, cleaner cut, while thicker wires are more robust for larger, denser polyps.

Procedural Technique: The snare is passed through the endoscope in a closed position. It is then opened and carefully maneuvered to encircle the base of the polyp. Once in position, the loop is slowly tightened, strangulating the polyp's stalk. An electrical current (cautery) is applied through the snare wire, which simultaneously cuts the polyp off and seals the blood vessels at the base to prevent bleeding. The severed polyp is then retrieved for analysis.

Managing acute gastrointestinal bleeding is a critical, life-saving application of endoscopy. Specialized therapeutic instruments are designed specifically for achieving hemostasis (stopping bleeding).

Injection Needles: These are retractable needles used to inject solutions directly into or around a bleeding site. The most common solution is diluted epinephrine, which causes the blood vessels to constrict, drastically reducing blood flow. Saline can also be injected to lift a lesion, making it easier to treat.

Hemoclips: These are small, metallic clips that function like surgical staples. The clip is housed in a deployment catheter. When a bleeding vessel is identified, the jaws of the clip are opened, positioned directly over the vessel, and then closed and deployed. The clip physically clamps the vessel shut, providing immediate and effective mechanical hemostasis. They are crucial for treating bleeding ulcers, diverticular bleeding, and post-polypectomy bleeding.

Band Ligators: These devices are used primarily to treat esophageal varices (swollen veins in the esophagus, common in patients with liver disease). A small elastic band is pre-loaded onto a cap at the tip of the endoscope. The varix is suctioned into the cap, and the band is deployed, effectively strangulating the varix and stopping blood flow.

These instruments are essential for safely removing objects from the GI tract. This can include foreign bodies that have been swallowed accidentally or intentionally, as well as excised tissue like large polyps or tumors.

Graspers and Forceps: Available in various jaw configurations (e.g., alligator, rat-tooth) to provide a secure grip on different types of objects, from sharp pins to soft food boluses.

Nets and Baskets: A retrieval net is a small, bag-like net that can be opened to capture an object and then closed securely for safe withdrawal. A wire basket (like a Dormia basket) is often used in ERCP to encircle and remove gallstones from the bile duct.

Accessory instruments are those that support the procedure, ensuring it can be performed safely, efficiently, and effectively. While they may not directly diagnose or treat, a procedure is often impossible without them.

Irrigation/Spray Catheters: A clear view is paramount in endoscopy. These catheters are used to spray jets of water to wash away blood, stool, or other debris that might obscure the physician's view of the mucosal lining.

Guidewires: In complex procedures like ERCP, a guidewire is an essential pathfinder. This very thin, flexible wire is advanced past a difficult stricture or into a desired duct. The therapeutic instruments (like a stent or dilation balloon) can then be passed over the guidewire, ensuring they reach the correct location.

Sphincterotomes and Papillotomes: Used exclusively in ERCP, a sphincterotome is an instrument with a small cutting wire at its tip. It is used to make a precise incision in the sphincter of Oddi (the muscular valve controlling the flow of bile and pancreatic juice), a procedure known as a sphincterotomy. This widens the opening, allowing for the removal of stones or the placement of stents.

The selection of endoscopic instruments is not arbitrary; it is a highly specific process dictated by the procedure being performed, the patient's anatomy, and the clinical objectives. A well-prepared endoscopy suite will have a vast array of instruments on hand to address any situation that may arise. The table below outlines the common instruments used in several key endoscopic procedures.

| Procedure | Primary Objective(s) | Primary Endoscopic Instruments Used | Secondary and Situational Endoscopic Instruments |

| Gastroscopy (EGD) | Diagnose and treat upper GI conditions (esophagus, stomach, duodenum). | - Standard Biopsy Forceps - Injection Needle | - Polypectomy Snare - Hemoclips - Retrieval Net - Dilation Balloon |

| Colonoscopy | Screen for and prevent colorectal cancer; diagnose colon diseases. | - Polypectomy Snare - Standard Biopsy Forceps | - Hot Biopsy Forceps - Hemoclips - Injection Needle - Retrieval Basket |

| ERCP | Diagnose and treat conditions of the bile and pancreatic ducts. | - Guidewire - Sphincterotome - Stone Retrieval Balloon/Basket | - Cytology Brush - Dilation Balloon - Plastic/Metal Stents - Biopsy Forceps |

| Bronchoscopy | Visualize and diagnose conditions of the airways and lungs. | - Cytology Brush - Biopsy Forceps | - Cryoprobe - Injection Needle - Foreign Body Grasper |

| Cystoscopy | Examine the lining of the bladder and urethra. | - Biopsy Forceps | - Stone Retrieval Basket - Electrocautery Probes - Injection Needle |

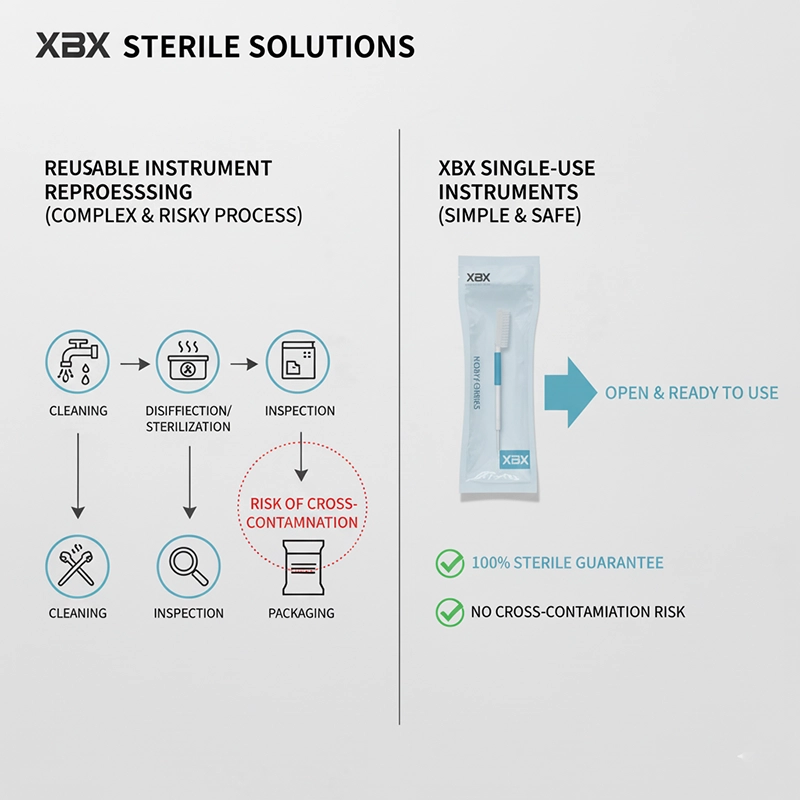

The safe and effective use of endoscopic instruments extends far beyond the procedure itself. Because these instruments come into contact with sterile and non-sterile body cavities and are reused on multiple patients, the process of cleaning and sterilization (known as reprocessing) is of paramount importance. Inadequate reprocessing can lead to the transmission of serious infections between patients.

The reprocessing cycle is a meticulous, multi-step protocol that must be followed without deviation:

Pre-Cleaning: This begins immediately at the point of use. The exterior of the instrument is wiped down, and the internal channels are flushed with a cleaning solution to prevent bio-burden (blood, tissue, etc.) from drying and hardening.

Leak Testing: Before immersion in fluids, flexible endoscopes are tested for leaks to ensure their internal components are not damaged.

Manual Cleaning: This is the most critical step. The instrument is completely immersed in a specialized enzymatic detergent solution. All external surfaces are brushed, and brushes of the appropriate size are passed through all internal channels multiple times to physically remove all debris.

Rinsing: The instrument is thoroughly rinsed with clean water to remove all traces of the detergent.

High-Level Disinfection (HLD) or Sterilization: The cleaned instrument is then either immersed in a high-level disinfectant chemical (like glutaraldehyde or peracetic acid) for a specific period and temperature or sterilized using methods like ethylene oxide (EtO) gas or hydrogen peroxide gas plasma. HLD kills all vegetative microorganisms, mycobacteria, and viruses but not necessarily high numbers of bacterial spores. Sterilization is a more absolute process that destroys all forms of microbial life.

Final Rinsing: Instruments are rinsed again, often with sterile water, to remove all chemical residues.

Drying and Storage: The instrument must be thoroughly dried inside and out, typically with forced filtered air, as moisture can promote bacterial growth. It is then stored in a clean, dry cabinet to prevent recontamination.

The complexity and critical nature of reprocessing have led to a major industry trend: the development and adoption of single-use, or disposable, endoscopic instruments. These instruments, such as biopsy forceps, snares, and cleaning brushes, are supplied in a sterile package, used for a single patient, and then safely discarded.

The advantages are compelling:

Elimination of Cross-Contamination Risk: The single greatest benefit is the complete removal of any risk of transmitting infections between patients via the instrument.

Guaranteed Performance: A new instrument is used every time, ensuring it is perfectly sharp, fully functional, and has no wear-and-tear, which can sometimes compromise the performance of reprocessed tools.

Operational Efficiency: It eliminates the time-consuming and labor-intensive reprocessing cycle, allowing for faster procedure turnaround times and freeing up technician staff for other duties.

Cost-Effectiveness: While there is a per-item cost, when the costs of labor, cleaning chemicals, repairs to reusable instruments, and the potential cost of treating a hospital-acquired infection are considered, disposable instruments are often highly cost-effective.

The field of endoscopic technology is in a constant state of innovation. The future promises even more remarkable capabilities, driven by advancements in robotics, imaging, and materials science. We are beginning to see the integration of robotic platforms that can provide superhuman stability and dexterity to endoscopic instruments. Artificial intelligence (AI) is being developed to assist in identifying suspicious lesions during a procedure in real-time. Furthermore, instruments are becoming smaller, more flexible, and more capable, allowing for procedures in previously inaccessible parts of the body.

In conclusion, endoscopic instruments are the heart of minimally invasive medicine. From the humble biopsy forceps that provides a definitive cancer diagnosis to the advanced hemoclip that stops life-threatening bleeding, these tools are indispensable. Their proper selection, use, and handling are fundamental to achieving positive patient outcomes. As technology continues to evolve, these instruments will only become more integral to the practice of medicine.

For healthcare facilities and practitioners looking to source high-quality, reliable, and technologically advanced endoscopic instruments, exploring a comprehensive catalog of both reusable and single-use options is the first step toward enhancing patient care and operational efficiency.

Endoscopic instruments are precision-engineered, specialized medical tools that are passed through the narrow channel of an endoscope to perform minimally invasive procedures. They allow physicians to perform actions such as taking biopsies, removing polyps, and stopping bleeding without the need for large, open surgical incisions.

Diagnostic instruments, such as biopsy forceps, are primarily used to gather information and tissue samples for an accurate diagnosis. Therapeutic instruments, such as polypectomy snares or hemostatic clips, are used to actively treat a condition discovered during the procedure.

The primary risk is cross-contamination. Due to the complex design of reusable instruments, the cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization process (known as "reprocessing") is extremely challenging. Authoritative bodies, including the FDA, have issued multiple safety warnings highlighting that inadequate reprocessing is a significant cause of patient-to-patient infections.

Single-use, or disposable, instruments offer three main advantages: 1 Absolute Safety: Each instrument is sterile-packed and used only once, fundamentally eliminating the risk of cross-contamination from improper reprocessing. 2 Reliable Performance: A new instrument is used every time, so there is no wear-and-tear from previous uses and cleaning cycles, ensuring optimal and consistent surgical performance. 3 Increased Efficiency: They eliminate the complex and time-consuming reprocessing workflow, reducing labor and chemical costs while improving turnaround times between procedures.

Copyright © 2025.Geekvalue All rights reserved.Technical Support:TiaoQingCMS