பொருளடக்கம்

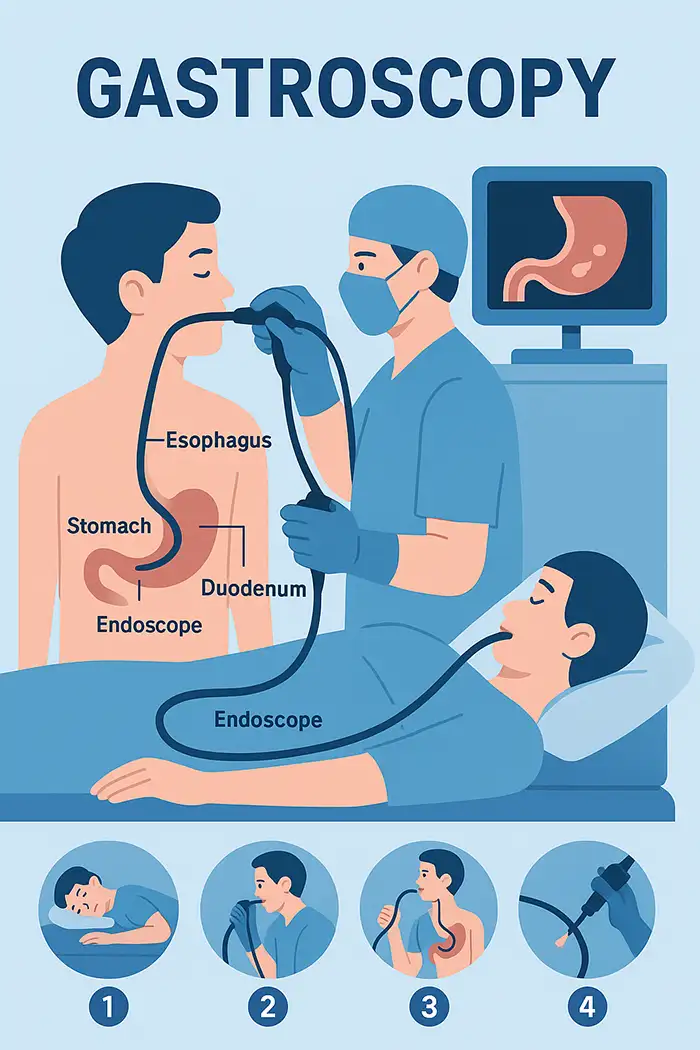

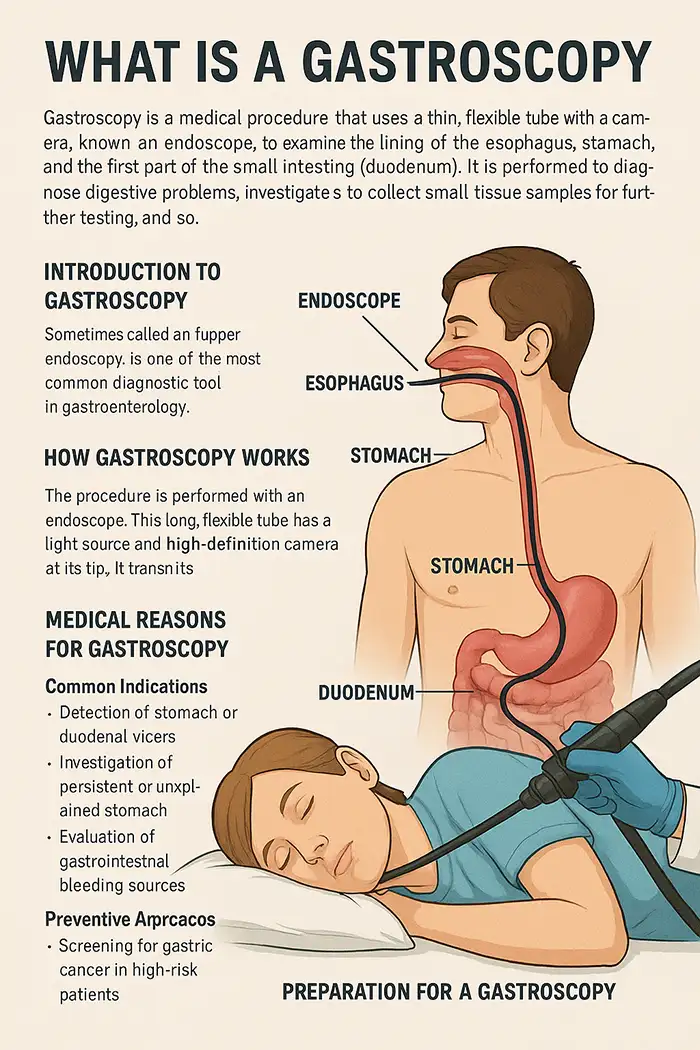

மேல் இரைப்பை குடல் (GI) எண்டோஸ்கோபி என்றும் அழைக்கப்படும் காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி, உணவுக்குழாய், வயிறு மற்றும் சிறுகுடலின் முதல் பகுதி (டியோடினம்) உள்ளிட்ட மேல் செரிமானப் பாதையை நேரடியாகக் காட்சிப்படுத்த அனுமதிக்கும் ஒரு குறைந்தபட்ச ஊடுருவும் மருத்துவ முறையாகும். இந்த செயல்முறை, உயர்-வரையறை கேமரா மற்றும் ஒளி மூலத்துடன் பொருத்தப்பட்ட காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப் எனப்படும் நெகிழ்வான குழாயைப் பயன்படுத்தி செய்யப்படுகிறது. காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபியின் முதன்மை நோக்கம், இரைப்பை குடல் நிலைமைகளைக் கண்டறிந்து சில நேரங்களில் சிகிச்சையளிப்பதாகும், இது எக்ஸ்-கதிர்கள் அல்லது CT ஸ்கேன்கள் போன்ற பிற இமேஜிங் முறைகளை விட மிகவும் துல்லியமான நிகழ்நேர படங்களை வழங்குகிறது.

காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி மருத்துவமனைகள், மருத்துவமனைகள் மற்றும் சிறப்பு இரைப்பை குடல் மையங்களில் நோயறிதல் மற்றும் சிகிச்சை நோக்கங்களுக்காக பரவலாகப் பயன்படுத்தப்படுகிறது. இரைப்பை அழற்சி, வயிற்றுப் புண்கள், பாலிப்ஸ், கட்டிகள் மற்றும் ஆரம்ப கட்ட புற்றுநோய்கள் போன்ற நிலைமைகளை அடையாளம் காண முடியும், மேலும் திசு பயாப்ஸிகளை ஹிஸ்டாலஜிக்கல் பகுப்பாய்விற்காக சேகரிக்கலாம். இந்த செயல்முறை பொதுவாக சிக்கலான தன்மையைப் பொறுத்து 15 முதல் 30 நிமிடங்கள் வரை ஆகும், மேலும் சிக்கல்களின் குறைந்த ஆபத்துடன் பாதுகாப்பானதாகக் கருதப்படுகிறது.

கடந்த தசாப்தங்களில் காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபியின் பரிணாமம், உயர்-வரையறை இமேஜிங், குறுகிய-பேண்ட் இமேஜிங் மற்றும் செயற்கை நுண்ணறிவு (AI) உடன் ஒருங்கிணைப்பு உள்ளிட்ட தொழில்நுட்பத்தில் ஏற்பட்ட முன்னேற்றங்களால் உந்தப்பட்டுள்ளது, இது மருத்துவர்கள் நுட்பமான சளிச்சவ்வு மாற்றங்களைக் கண்டறிந்து நோயறிதலின் துல்லியத்தை மேம்படுத்த உதவுகிறது.

காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி உணவுக்குழாய், வயிறு மற்றும் டியோடெனம் ஆகியவற்றின் நேரடி காட்சிப்படுத்தலை வழங்குகிறது.

இரைப்பை அழற்சி, புண்கள், பாரெட்டின் உணவுக்குழாய் அல்லது ஆரம்ப கட்ட இரைப்பை புற்றுநோய் போன்ற நிலையான இமேஜிங் மூலம் தெரியாத நிலைமைகளை இது கண்டறிகிறது.

ஒரே நேரத்தில் நோயறிதல் மதிப்பீடு மற்றும் சிகிச்சை தலையீடுகளை அனுமதிக்கிறது.

தொடர்ந்து மேல் வயிற்று வலி, விவரிக்கப்படாத இரைப்பை குடல் இரத்தப்போக்கு அல்லது நாள்பட்ட ரிஃப்ளக்ஸ் உள்ள நோயாளிகளுக்கு இது முக்கியமானது.

ஹிஸ்டோபோதாலஜிக்கல் மதிப்பீட்டிற்கான திசு பயாப்ஸிகளை செயல்படுத்துகிறது, இது H. பைலோரி தொற்று, செலியாக் நோய் அல்லது ஆரம்பகால கட்டிகளைக் கண்டறிவதற்கு முக்கியமானது.

புற்றுநோய்க்கு முந்தைய புண்களை முன்கூட்டியே கண்டறிவதன் மூலம் தடுப்பு மருத்துவத்தை ஆதரிக்கிறது.

பல வருகைகளுக்கான தேவையைக் குறைத்து உடனடி தலையீட்டை அனுமதிக்கிறது.

நோயாளி பராமரிப்பு, ஆரம்பகால கண்டறிதல் மற்றும் சிகிச்சை விளைவுகளை மேம்படுத்துகிறது.

உயர்-வரையறை கேமரா மற்றும் ஒளி மூலத்துடன் கூடிய நெகிழ்வான குழாய்.

வேலை செய்யும் சேனல்கள் பயாப்ஸி, பாலிப் அகற்றுதல், ஹீமோஸ்டாஸிஸ் அல்லது சைட்டாலஜி ஆகியவற்றை அனுமதிக்கின்றன.

மேம்பட்ட அம்சங்கள்: குறுகிய-பட்டைப் படமாக்கல், உருப்பெருக்கம், குரோமோஎண்டோஸ்கோபி, டிஜிட்டல் மேம்பாடு.

ஆவணங்கள் அல்லது தொலை மருத்துவத்திற்கான நிகழ்நேர வீடியோவைப் பதிவுசெய்தல் மற்றும் சேமிப்பதை ஆதரிக்கிறது.

நோயாளி இடது பக்கத்தில் படுத்துக் கொண்டுள்ளார்; உள்ளூர் மயக்க மருந்து அல்லது லேசான மயக்க மருந்து பயன்படுத்தப்படுகிறது.

வாய் வழியாக காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப் செருகப்பட்டு, உணவுக்குழாய், வயிறு மற்றும் டியோடெனம் வழியாக செல்கிறது.

அசாதாரணங்களுக்காக சளிச்சவ்வு பரிசோதிக்கப்பட்டது; தேவைப்பட்டால் பயாப்ஸிகள் அல்லது சிகிச்சை தலையீடுகள் செய்யப்படுகின்றன.

ஆவணப்படுத்தலுக்காக உயர்-வரையறை மானிட்டரில் காட்டப்படும் படங்கள்.

மேல் இரைப்பை குடல் இரத்தப்போக்கை மதிப்பிடுகிறது மற்றும் சிகிச்சை தளங்களைக் கண்டறிகிறது.

அதிக ஆபத்துள்ள நோயாளிகள் புற்றுநோய்க்கு முந்தைய மாற்றங்களுக்கு முன்கூட்டியே பரிசோதிக்கப்பட்டனர்.

பாரெட்டின் உணவுக்குழாய் போன்ற நாள்பட்ட நிலைமைகளைக் கண்காணிக்கிறது.

விரிவான பராமரிப்புக்காக பயாப்ஸி, இரத்தப் பரிசோதனைகள் அல்லது ஹெச். பைலோரி பரிசோதனையுடன் இணைந்து.

மேல் வயிற்று வலி அல்லது டிஸ்ஸ்பெசியா தொடர்ந்து இருப்பது.

இரத்தப்போக்கு அல்லது அடைப்பை ஏற்படுத்தும் இரைப்பை அல்லது சிறுகுடல் புண்களைக் கண்டறிதல்.

இரைப்பை குடல் இரத்தப்போக்கு மதிப்பீடு (ஹீமாடெமிசிஸ் அல்லது மெலினா).

இரைப்பை அழற்சி, உணவுக்குழாய் அழற்சி அல்லது பாரெட்டின் உணவுக்குழாய் ஆகியவற்றைக் கண்காணித்தல்.

எச். பைலோரி தொற்று நோய் கண்டறிதல்.

அதிக ஆபத்துள்ள நோயாளிகளில் இரைப்பை மற்றும் உணவுக்குழாய் புற்றுநோய்க்கான பரிசோதனை.

டிஸ்ப்ளாசியா அல்லது அடினோமாக்களை முன்கூட்டியே கண்டறிதல்.

வாழ்க்கை முறை தொடர்பான காரணிகளுக்கான (மது, புகைத்தல், உணவுமுறை) ஆபத்து வகைப்பாடு.

இரைப்பை அறுவை சிகிச்சை அல்லது சிகிச்சைக்குப் பிறகு அறுவை சிகிச்சைக்குப் பிந்தைய கண்காணிப்பு.

50 வயதுக்கு மேற்பட்ட நோயாளிகளுக்கு அல்லது அதிக பாதிப்பு உள்ள பகுதிகளில் வழக்கமான பரிசோதனை.

வயிறு காலியாக இருப்பதை உறுதி செய்ய 6–8 மணி நேரம் உண்ணாவிரதம் இருக்க வேண்டும்.

தேவைப்பட்டால் இரத்தத்தை மெலிக்கும் மருந்துகளை சரிசெய்யவும்.

ஒவ்வாமை மற்றும் முந்தைய மயக்க மருந்து எதிர்வினைகள் உட்பட முழுமையான மருத்துவ வரலாற்றை வழங்கவும்.

செயல்முறைக்கு முன் புகைபிடித்தல், மது அருந்துதல் மற்றும் சில மருந்துகளைத் தவிர்க்கவும்.

செயல்முறை, நோக்கம், அபாயங்கள் மற்றும் எதிர்பார்க்கப்படும் விளைவுகளை விளக்குங்கள்.

பதட்டம் அல்லது கிளாஸ்ட்ரோஃபோபியாவை நிவர்த்தி செய்யுங்கள்.

நோய் கண்டறிதல் மற்றும் சிகிச்சை நோக்கங்களுக்காக தகவலறிந்த ஒப்புதலைப் பெறுங்கள்.

மயக்க மருந்து பயன்படுத்தப்பட்டால், செயல்முறைக்குப் பிறகு போக்குவரத்தை ஏற்பாடு செய்யுங்கள்.

முக்கிய அறிகுறிகளை தொடர்ந்து கண்காணித்தல்.

நுட்பமான புண்கள் காணாமல் போவதைத் தவிர்க்க முறையான பரிசோதனை.

தேவைப்பட்டால் பயாப்ஸிகள் சேகரிக்கப்பட்டு சிகிச்சை நடைமுறைகள் செய்யப்படுகின்றன.

அசாதாரண கண்டுபிடிப்புகள் ஆவணப்படுத்தப்பட்டுள்ளன; படங்கள்/வீடியோ பதிவுகளுக்காக சேமிக்கப்பட்டுள்ளன.

லேசான அழுத்தம், வீக்கம் அல்லது தொண்டை வலி பொதுவானது ஆனால் தற்காலிகமானது.

மயக்க மருந்து அல்லது உள்ளூர் மயக்க மருந்து அசௌகரியத்தைக் குறைக்கிறது.

செயல்முறைகள் 15–30 நிமிடங்கள் நீடிக்கும்; 1–2 மணி நேரத்தில் குணமடைவார்கள்.

வழக்கமான செயல்பாடுகளை படிப்படியாகத் தொடங்குங்கள்; உணவு மற்றும் நீரேற்றம் பற்றிய ஆலோசனையைப் பின்பற்றுங்கள்.

வலி, மயக்கம், வாந்தி எடுக்கும் நேரம், செயல்முறையின் காலம் மற்றும் உடற்கூறியல் ஆகியவற்றைப் பொறுத்தது.

மயக்க மருந்தின் கீழ் உள்ள நோயாளிகள் பொதுவாக மிகக் குறைந்த அசௌகரியத்தையே உணர்வார்கள்.

மேற்பூச்சு மயக்க மருந்து ஸ்ப்ரேக்கள் அல்லது ஜெல்கள் வாந்தியைத் தடுக்கும் விளைவைக் குறைக்கின்றன.

லேசான IV மயக்க மருந்து தளர்வை உறுதி செய்கிறது.

சுவாசம் மற்றும் தளர்வு நுட்பங்கள் ஆறுதலுக்கு உதவுகின்றன.

அனுபவம் வாய்ந்த எண்டோஸ்கோபிஸ்ட்டின் மென்மையான நுட்பம் மன அழுத்தத்தைக் குறைக்கிறது.

தொண்டையில் லேசான எரிச்சல் அல்லது வலி.

பயாப்ஸி இரத்தப்போக்குக்கான சிறிய ஆபத்து, பொதுவாக தானாகவே சரியாகிவிடும்.

அரிதாக: துளைத்தல், தொற்று அல்லது மயக்க எதிர்வினை.

கடுமையான இதய நுரையீரல் நோயாளிகளுக்கு கூடுதல் கண்காணிப்பு தேவைப்படுகிறது.

எண்டோஸ்கோப்புகளின் கடுமையான கிருமி நீக்கம்.

பயிற்சி பெற்ற ஊழியர்களால் மயக்க மருந்து கண்காணிக்கப்பட்டது.

சிக்கல்களுக்கு அவசரகால நெறிமுறைகள் தயாராக உள்ளன.

பாதுகாப்பு மற்றும் நோயாளி பராமரிப்புக்கான வழக்கமான பணியாளர் பயிற்சி.

இரைப்பை அழற்சி, உணவுக்குழாய் அழற்சி, சளி சவ்வு வீக்கம், வயிற்றுப் புண்கள்.

இரைப்பை குடல் இரத்தப்போக்கு, பாலிப்ஸ், கட்டிகள், எச். பைலோரி தொற்றுக்கான ஆதாரங்கள்.

புற்றுநோய்க்கு முந்தைய புண்கள், பாரெட்டின் உணவுக்குழாய், ஆரம்பகால இரைப்பை புற்றுநோய்.

நாள்பட்ட நிலைமைகள்: மீண்டும் மீண்டும் வரும் இரைப்பை அழற்சி, ரிஃப்ளக்ஸ், அறுவை சிகிச்சைக்குப் பிந்தைய மாற்றங்கள்.

உடற்கூறியல் அசாதாரணங்கள்: இறுக்கங்கள், ஹைட்டல் குடலிறக்கம்.

எக்ஸ்-கதிர்கள்: கட்டமைப்பு பார்வை, பயாப்ஸி இல்லை.

CT ஸ்கேன்கள்: குறுக்கு வெட்டு படங்கள், வரையறுக்கப்பட்ட சளிச்சவ்வு விவரங்கள்.

காப்ஸ்யூல் எண்டோஸ்கோபி: சிறுகுடலை காட்சிப்படுத்துகிறது, ஆனால் பயாப்ஸி/தலையீடு இல்லை.

நேரடி காட்சிப்படுத்தல், பயாப்ஸி திறன், ஆரம்பகால புண் கண்டறிதல், சிகிச்சை தலையீடுகள்.

பல நோயறிதல் வருகைகளுக்கான தேவையைக் குறைக்கிறது.

குறைந்தபட்ச ஊடுருவும் சிகிச்சையை செயல்படுத்துகிறது.

மயக்கம் நீங்கும் வரை கவனித்தல் (30–60 நிமிடங்கள்).

ஆரம்பத்தில் மென்மையான உணவுகள் மற்றும் நீரேற்றம்.

லேசான வீக்கம், வாயு அல்லது தொண்டை அசௌகரியம் பொதுவாக விரைவாகக் குணமாகும்.

கடுமையான வயிற்று வலி, வாந்தி அல்லது இரத்தப்போக்கு ஏற்பட்டால் உடனடியாகப் புகாரளிக்கவும்.

பயாப்ஸி முடிவுகள் மற்றும் பின்தொடர்தல் மேலாண்மையை மதிப்பாய்வு செய்யவும்.

நாள்பட்ட அல்லது சிகிச்சைக்குப் பிந்தைய நிலைமைகளுக்கு அவ்வப்போது கண்காணிப்பு.

சிறந்த புண் கண்டறிதலுக்கான உயர்-வரையறை இமேஜிங், குறுகிய-பட்டை இமேஜிங், குரோமோஎண்டோஸ்கோபி, 3D காட்சிப்படுத்தல்.

AI-உதவி கண்டறிதல் மனிதப் பிழைகளைக் குறைத்து நிகழ்நேர நோயறிதலை ஆதரிக்கிறது.

புதிய எண்டோஸ்கோபிஸ்டுகளுக்கு சந்தேகத்திற்கிடமான பகுதிகளை முன்னிலைப்படுத்துவதன் மூலம் AI பயிற்சிக்கு உதவுகிறது.

அறுவை சிகிச்சை இல்லாமல் கட்டியை முன்கூட்டியே அகற்றுவதற்கான எண்டோஸ்கோபிக் சளிச்சவ்வு பிரித்தல்.

ஹீமோஸ்டேடிக் நுட்பங்கள் இரத்தப்போக்கை திறம்பட கட்டுப்படுத்துகின்றன.

மேம்பட்ட சாதனங்கள் பாலிப்கள் மற்றும் ஸ்ட்ரிக்சர்களுக்கு குறைந்தபட்ச ஊடுருவும் தலையீடுகளை செயல்படுத்துகின்றன.

விட்டம், நெகிழ்வுத்தன்மை, படத் தெளிவுத்திறன் ஆகியவற்றை மதிப்பிடுங்கள்.

சப்ளையர் நற்பெயர், சான்றிதழ்கள், சேவை தரம் ஆகியவற்றைக் கருத்தில் கொள்ளுங்கள்.

பயாப்ஸி, உறிஞ்சுதல் மற்றும் சிகிச்சை கருவிகளுடன் இணக்கத்தன்மையை உறுதி செய்யவும்.

அதிகபட்ச மருத்துவ மதிப்பிற்கு செலவு மற்றும் தரத்தை சமநிலைப்படுத்துங்கள்.

உத்தரவாதம், பராமரிப்பு மற்றும் பயிற்சி ஆதரவைக் கருத்தில் கொள்ளுங்கள்.

மருத்துவ தேவையின் அடிப்படையில் மொத்த கொள்முதல் vs. ஒற்றை-அலகு கொள்முதல்.

காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி என்பது நவீன இரைப்பை குடல் மருத்துவத்தில் ஒரு தவிர்க்க முடியாத கருவியாகும், இது நோயறிதல் துல்லியம், தடுப்பு பரிசோதனை மற்றும் சிகிச்சை திறன் ஆகியவற்றை ஒருங்கிணைக்கிறது. மேல் இரைப்பை குடல் பாதையை நேரடியாக காட்சிப்படுத்துதல், பயாப்ஸிகளை சேகரித்தல் மற்றும் ஆரம்பகால புண்களைக் கண்டறிதல் ஆகியவற்றின் திறன், வழக்கமான பராமரிப்பு மற்றும் அதிக ஆபத்துள்ள நோயாளி கண்காணிப்பு இரண்டிலும் இதை விலைமதிப்பற்றதாக ஆக்குகிறது. உயர்-வரையறை இமேஜிங், குறுகிய-பேண்ட் இமேஜிங் மற்றும் AI-உதவி கண்டறிதல் போன்ற தொழில்நுட்ப முன்னேற்றங்கள் நோயறிதல் துல்லியம் மற்றும் நோயாளி ஆறுதல் இரண்டையும் மேம்படுத்தியுள்ளன. சரியான தயாரிப்பு, பாதுகாப்பு நெறிமுறைகள் மற்றும் செயல்முறைக்குப் பிந்தைய பராமரிப்பு ஆகியவை உகந்த விளைவுகளை மேலும் உறுதி செய்கின்றன. உயர்தர உபகரணங்கள் மற்றும் நம்பகமான சப்ளையர்களைத் தேர்ந்தெடுப்பது செயல்திறன், பாதுகாப்பு மற்றும் நோயாளி பராமரிப்பை மேம்படுத்துகிறது. குறைந்தபட்ச ஊடுருவும் இரைப்பை குடல் நோயறிதலில் காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி முன்னணியில் உள்ளது, ஆரம்பகால தலையீடு, தடுப்பு மருத்துவம் மற்றும் மேம்பட்ட நோயாளி வாழ்க்கைத் தரத்தில் முக்கிய பங்கு வகிக்கிறது.

மருத்துவமனைகள் நிலையான நோயறிதல் காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப்புகள், பெரிய வேலை சேனல்களைக் கொண்ட சிகிச்சை காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப்புகள் மற்றும் உயர்-வரையறை இமேஜிங் அல்லது குறுகிய-பட்டைப் இமேஜிங்கைக் கொண்ட மேம்பட்ட மாதிரிகள் ஆகியவற்றிலிருந்து தேர்ந்தெடுக்கலாம்.

அனைத்து காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோபி சாதனங்களும் ISO மற்றும் CE சான்றிதழ்களுடன் இணங்க வேண்டும், மேலும் சப்ளையர்கள் தர உத்தரவாத அறிக்கைகள், கருத்தடை சரிபார்ப்பு மற்றும் ஒழுங்குமுறை இணக்க ஆவணங்களை வழங்க வேண்டும்.

ஆம், நவீன காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப்புகளில் பயாப்ஸி ஃபோர்செப்ஸிற்கான வேலை செய்யும் சேனல்கள், பாலிப் அகற்றும் கருவிகள் மற்றும் ஹீமோஸ்டேடிக் சாதனங்கள் ஆகியவை அடங்கும், இது நோயறிதல் மற்றும் சிகிச்சை நடைமுறைகளை அனுமதிக்கிறது.

நுண்ணிய சளிச்சவ்வு மாற்றங்களைக் கண்டறிவதற்கும் நோயறிதல் துல்லியத்தை மேம்படுத்துவதற்கும் உயர்-வரையறை இமேஜிங், குறுகிய-பேண்ட் இமேஜிங் மற்றும் டிஜிட்டல் குரோமோஎண்டோஸ்கோபி ஆகியவை பரிந்துரைக்கப்படுகின்றன.

பெரும்பாலான சப்ளையர்கள் நீண்ட கால நம்பகத்தன்மையை உறுதி செய்வதற்காக 1–3 வருட உத்தரவாதம், தடுப்பு பராமரிப்பு, ஆன்-சைட் தொழில்நுட்ப ஆதரவு மற்றும் உதிரி பாகங்கள் கிடைப்பதை வழங்குகிறார்கள்.

ஆம், பல மேம்பட்ட காஸ்ட்ரோஸ்கோப்புகள் தொலைதூர ஆலோசனைக்காக டிஜிட்டல் வீடியோ பதிவு, சேமிப்பு மற்றும் PACS அல்லது டெலிமெடிசின் தளங்களுடன் ஒருங்கிணைப்பை ஆதரிக்கின்றன.

நோயாளியின் பாதுகாப்பு மற்றும் மருத்துவமனை தரநிலைகளுக்கு இணங்குவதை உறுதி செய்வதற்கு, முறையான கருத்தடை நெறிமுறைகள், கண்காணிக்கப்பட்ட மயக்க மருந்து மற்றும் அவசரகால நடைமுறைகளில் பயிற்சி பெற்ற ஊழியர்கள் அவசியம்.

சப்ளையர்கள் பெரும்பாலும் ஆன்-சைட் பயிற்சி, பயனர் கையேடுகள் மற்றும் டிஜிட்டல் பயிற்சிகளை வழங்குகிறார்கள், மேலும் AI-உதவி எண்டோஸ்கோபி போன்ற மேம்பட்ட நுட்பங்களுக்கான பட்டறைகளை வழங்கலாம்.

நோயாளியின் ஆறுதல் மற்றும் தொற்று கட்டுப்பாட்டிற்காக பயாப்ஸி ஃபோர்செப்ஸ், சைட்டாலஜி தூரிகைகள், ஊசி ஊசிகள், சுத்தம் செய்யும் தூரிகைகள் மற்றும் பயன்படுத்திவிட்டு தூக்கி எறியக்கூடிய மவுத்கார்டுகள் ஆகியவை பொதுவான துணைப் பொருட்களில் அடங்கும்.

கொள்முதல் குழுக்கள் உபகரணங்களின் விவரக்குறிப்புகள், விற்பனைக்குப் பிந்தைய ஆதரவு, உத்தரவாத விதிமுறைகள் மற்றும் பயிற்சி சேவைகளை ஒப்பிட்டுப் பார்க்க வேண்டும், நிரூபிக்கப்பட்ட மருத்துவ அனுபவம் மற்றும் சான்றிதழ் இணக்கம் கொண்ட சப்ளையர்களைத் தேர்ந்தெடுக்க வேண்டும்.

பதிப்புரிமை © 2025. கீக்வேல்யூ அனைத்து உரிமைகளும் பாதுகாக்கப்பட்டவை.தொழில்நுட்ப உதவி: TiaoQingCMS